Part 1 of the “Scent and the Roman Empire” Series

Walk down a street in ancient Rome, and your senses would be overwhelmed—not just by the grandeur of marble columns or the rumble of chariot wheels, but by the invisible presence of scent. In the Roman world, fragrance was more than a luxury. It was an unspoken language of identity, class, politics, and divine connection.

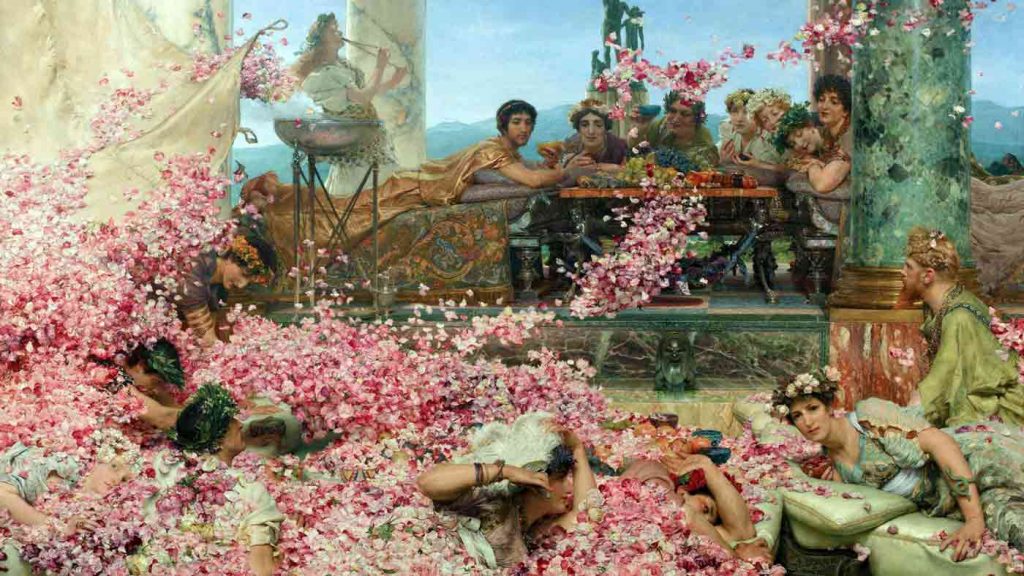

Romans made frequent use of perfumed oils, or unguenta. After bathing in the thermae, people—especially the elite—would anoint their bodies with aromatic oils infused with ingredients like myrrh, frankincense, rose, and cinnamon. These unguenta were not just about hygiene or beauty; they were a marker of status, a sensory display of one’s social rank. Women of high society would perfume not only their skin and hair, but even their curtains and bed linens with fragrant oils.

Yet Rome was not the birthplace of this olfactory culture—it was its grandest consumer. The Roman Empire absorbed and reinterpreted fragrance traditions from the Egyptians, Persians, Greeks, and Arabian cultures. Rare aromatics and spices were imported through vast trade networks from Egypt, Arabia, and India, often arriving at the Roman port of Ostia via Alexandria. Some of these imported resins were valued more than gold.

In Egypt, incense was seen as a sacred offering to the gods. Rome adopted this belief and incorporated incense rituals into its own religious ceremonies. In Roman temples, thuribula—bronze censers—were used to burn incense as part of sacrifices and rites. Fragrance also played a vital role in funeral practices, believed to purify and sanctify the deceased before their journey to the afterlife.

While the Greeks saw fragrance as part of personal refinement and the Egyptians as a divine connection, the Romans transformed it into a symbol of power. Emperor Nero, infamous for his extravagance, reportedly burned an entire year’s worth of Rome’s incense reserves at the funeral of his wife, Poppaea. Historical sources claim the air was so thick with scent that it seemed the heavens themselves were perfumed.

In Rome, fragrance was intangible yet omnipresent—woven into every layer of society, from temple altars to private baths. A single drop of perfumed oil could distinguish a patrician from a plebeian. A wisp of incense smoke could bridge the mortal and the divine. This was an empire scented not only with power, but with memory—a civilization remembered by its perfume.

Coming Next: “Fragrance and Power: The Political Scent of the Roman Elite”

Leave a comment