A story of incense, power, and the divine femininity of Egypt’s forgotten ruler

In the heart of ancient Thebes, long before Cleopatra seduced Rome and before Nefertiti redefined elegance, a woman dared to do the unthinkable — she became Pharaoh. Not queen, not consort. Pharaoh.

Her name was Hatshepsut.

And her rule, scented with sacred incense and cloaked in divine authority, remains one of the most fascinating chapters in Egypt’s history.

Born to Pharaoh Thutmose I and Queen Ahmose, Hatshepsut was not meant to rule. But when her husband-brother Thutmose II died, and her stepson was still a child, she stepped into power — slowly at first, as regent. Then, boldly, as Pharaoh in her own name.

She didn’t disguise herself as a woman. She transcended gender. Wearing the traditional false beard of a king and royal male garb, she commissioned grand monuments, expanded trade, and restructured religious practices — all while reinforcing that her rule was ordained by the gods.

But her power wasn’t just in temples and politics.

It was also in scent — specifically, in incense.

Hatshepsut’s most ambitious journey was the legendary expedition to the Land of Punt, a distant and mysterious region believed to lie in the Horn of Africa. She sent fleets not to conquer, but to trade. Their most prized cargo?

Frankincense trees. Myrrh. Cinnamon. Exotic resins.

She didn’t just bring back incense — she brought back the source. Her temple at Deir el-Bahari, nestled beneath the cliffs of western Thebes, is adorned with carved scenes of this voyage. Inscriptions detail the trees being planted in the temple gardens — the first recorded botanical transplant in history.

Why was incense so important?

In ancient Egypt, incense was more than aroma. It was a conduit to the divine. Burned in temples during rituals, it purified space, summoned deities, and embodied the breath of the gods. To command incense was to command the sacred.

By controlling the incense trade and planting it within the temple itself, Hatshepsut wasn’t just importing scent.

She was anchoring her reign in spiritual legitimacy — making her rule inseparable from the divine.

This move was brilliant. Political. Theological. Sensory.

A queen turned king, perfumed in sacred smoke.

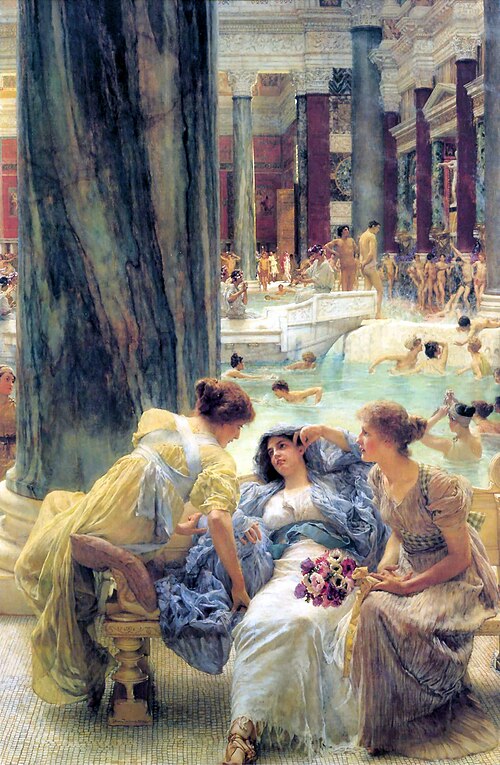

Even the architecture of her temple evokes this sensual sacredness: open courtyards bathed in sunlight, smooth limestone walls echoing chants, and faint trails of myrrh and kyphi (a temple blend of resins, honey, and wine) rising into the desert sky.

Yet after her death, her memory was nearly erased — statues defaced, her name chiseled out. Historians long believed this was done by her jealous stepson, but modern research suggests it may have been a calculated political move to restore dynastic clarity.

But memory, like scent, lingers in the air long after the source is gone.

Today, Hatshepsut is celebrated as one of history’s first great female rulers — a leader who used not only power and architecture, but the deep magic of perfume and ritual, to shape her empire.

Her story reminds us:

True authority doesn’t always roar. Sometimes, it rises slowly — like incense — and fills the world with something unforgettable.

Love stories like this?

My new digital book Eternal Queens explores the sacred scent rituals of Egypt’s most powerful women—Cleopatra, Nefertiti, and Ankhesenamun—through history, myth, and modern blends.

🌿 Includes printable ritual cards and fragrance recipes.

👉 Download it now

Coming Next: “Ancient Scents & Beauty Rituals: Oils, Powders, and Perfumes of the Nile”

👉 Dive into the natural ingredients and sacred blends behind Egyptian beauty and wellness.