Part 2 of the “Scent and the Roman Empire” Series

“Scent was not only a pleasure of the body, but a message to the world.”

In ancient Rome, scent wasn’t just a matter of pleasure—it was a political statement. The fragrances worn, burned, and bathed in by the Roman elite carried as much meaning as their togas, villas, or marble busts. In the hands of Rome’s most powerful figures, scent became a subtle but potent tool of persuasion, diplomacy, and dominance.

One of the most legendary examples of this olfactory diplomacy is the relationship between Julius Caesar and Cleopatra. When the Egyptian queen first sailed to meet Caesar, historical accounts tell us that her arrival was heralded not just by music and finery, but by the overwhelming scent of incense and exotic oils that perfumed the sails of her barge. Cleopatra had mastered the use of fragrance as a sensory weapon—one that conveyed wealth, mystery, and divine allure. For Roman observers, the air around her was more than scented—it was charged with meaning, seduction, and power.

Caesar, a master of public image himself, understood the significance of such theatrics. Though Romans traditionally praised stoicism and modesty, the upper class increasingly embraced luxury as a sign of dominance. Fragrance, imported at great cost from the East, became a public display of imperial reach. To smell of frankincense or myrrh was to smell like the empire itself—vast, powerful, and irresistible.

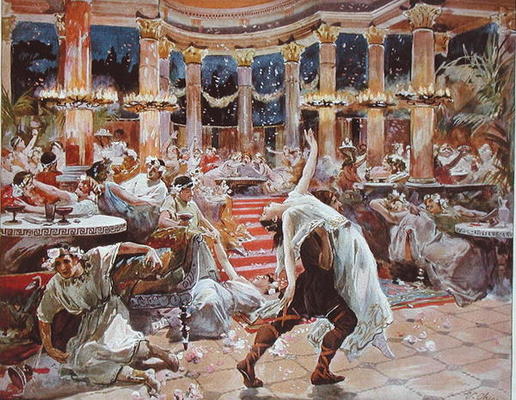

Later emperors would take this to the extreme. Nero, infamous for extravagance, was said to have perfumed banquet halls with ceilings that rained down rose petals and unguents. His palace was designed with pipes that released fragrant vapors into the air, turning architecture into olfactory theater. His use of scent was not just indulgent; it was political—declaring his divine status through overwhelming sensory experience.

Even the rituals of the Roman Senate and state religion were filled with fragrant symbolism. Incense was burned during official ceremonies not only to honor the gods but to create an atmosphere of solemnity and control. The more lavish the scent, the more powerful the presence.

Among aristocrats, the use of rare and complex perfumes became a competitive art. Recipes were closely guarded, and perfumers gained celebrity status in certain circles. Fragrance was worn not only on the body, but in rings with secret scent compartments, in hair oils, and even mixed into wine. It was whispered that you could tell a man’s political aspirations by the way he smelled—and whether his fragrance lingered after he left the room.

In Rome, power didn’t just speak. It perfumed.

It left behind a trail—not just of influence, but of scent.

And in a city obsessed with legacy, to be remembered by your fragrance was as enduring as any statue.

Coming Next: “Fragrance in Everyday Roman Life”

Leave a comment